Veteran of four wars, four enlistments, four branches: Air Force, Army, Army Reserve, Army National Guard. I am both an AF (Air Force) veteran and as Veteran AF (As Fuck)

Sunday, February 4, 2018

Immigration and Surviving The Holocaust in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

On the eve of World War in the late 1930s, the original "America First" campaign turned away thousands of Jews who came to America to escape the Holocaust.

But more than twenty Jewish families that escaped Germany and the Nazis found refuge in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a haven for refugees then and now.

One of those refugees died on February first. Just a young boy when he arrived here with his parents, Arno Gerhard "Gary" Wolff of Millersville was 83.

Born in Schneidemühl, Germany, he was the son of the late Kurt and Else Rothschild Wolff. Arno had two older brothers who stayed behind in Germany. They were both sure that things would get better. Both were lost in the Holocaust.

The two older brothers were murdered by the Nazis. Arno and his parents, while fortunate to get out of Germany, were left to deal with the scar of the murder of their Arno's older brothers, the sons of Kurt and Else.

Arno Wolff had a long and successful life in America. He taught as a Professor in colleges and universities in both the United States and Germany. But he and his parents lived with a loss from which no one fully recovers.

Nazis are not "fine people." Not here, not anywhere, not ever.

Who Fights Our Wars? "Doc" Dreher, Blackhawk Pilot

Darren "Doc" and Kate Dreher at the Aviation Ball

Through Facebook, I just saw that a friend I deployed with

in 2009-10 is off to another overseas adventure.

Darren “Doc” Dreher is a Blackhawk pilot. We first met

during training for deployment to Iraq. We were at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, getting

ready to fly to Kuwait and meet up with our helicopters and equipment. Then we

went into Iraq.

Like nearly everyone in the 28th Combat Aviation

Brigade, Pennsylvania Army National Guard, Doc is from the mid state, not the

city. He lives in vast 570 area code

that, together with 814 covers the majority of the population of the Keystone

State.

When Doc and I first started talking it was because one of

the other pilots let him know there was an old sergeant who was a liberal in

Echo Company. We started arguing about

whether the TEA Party were just the nicest, cleanest most well-behaved people

who ever graced the National Mall with their presence, or they were

out-of-the-closet racists trumpeting Birther and other conspiracies inflamed by

idiots like Glenn Beck. That was the starting point for several discussions.

Believe it or not, we kept talking. We could clear a room with soldiers rolling

their eyes about more political bullshit, but they could also see we were

having fun. Doc is smart and quick and

won most of our discussions. In fact, it

was pretty clear after a while that he continued the arguments for his own

amusement. He would smile just a little before announcing the latest outrage by

President Obama.

But Doc is not just razor wit and a pretty face (there were

many jokes about which of us was better looking), he was by every indication I

could see an amazing pilot. It seemed everyone wanted to fly with him, both

other flight crew members and the soldiers we carried on missions. One time I flew with Doc was up to Camp Garry

Owen on the Iran-Iraq border. On the

flight was Colonel Peter Newell, commander of the 4th Brigade, 1st

Armored, the unit that provided security for our main base at Camp Adder. Newell put his unit patch on the nose of

Doc’s Blackhawk helicopter. So when

Newell went to the border to oversee anti-smuggling operations or some other

mission, Doc was often his pilot.

"Doc" Dreher flying over the Ziggurat of Ur

Another time I got to fly with Doc was for a video camera

crew visiting Camp Adder. I think it was a British crew, but it may have been a

British cameraman working for an American network. The camera crew wanted to get a flyover shot

of the Ziggurat of Ur, a huge monument to the prophet Abraham that was close to

our base. The wind howled out of the

west most days. Doc hovered a hundred feet above the Ziggurat and a few miles

west with the aircraft perpendicular to the wind. When the cameraman was ready

to roll film, Doc trimmed the rotor blades and we flew sideways at 30 knots

with the doors fully open. It was spooky

and exciting to be moving only sideways. I had taken some weird twists and

turns flying in Army helicopters, but flying completely sideways was new to me.

After Iraq, I saw Doc only occasionally, if I happened to be

on flight when he was on duty, or at the annual Aviation Ball with his wife

Kate. He first introduced me to Kate as his “favorite liberal.” Wherever he is, I hope Doc finds another

liberal to argue with. Defending myself from Doc’s wit and encyclopedic

knowledge made me a better liberal. Thanks Doc!

I hope

my favorite conservative has a safe deployment. And Congratulations on your promotion to Chief Warrant Officer 5.

-->

Thursday, February 1, 2018

When is an Old Soldier Really Old?

Young People, whatever their age, take needless, thrilling risks

A 58-year-old retired sergeant major I served with in the 70th Armor said yesterday, in a discussion we were having about Life, that he is not old. I made a joke about it saying he is, in fact, old. He persisted in denying it.

For me, the first measure of being old is in the effect of training on my bicycle racing. Training in my mid-60s does not make me better, it helps me to get worse at a slower rate. I will never be faster climbing a two-mile hill than I was when I was forty. If I train hard, I get slower at a slower rate. That is the effect of old age on my body. It is inevitable and predictable and responds well to exercise.

The soul is just as predictable. When people get old in their souls, their hope is in restoring the past, not striving to the future. Ironically, though they are nearer death and have less to lose than a 20-year-old in terms of life lived, the old soul stops taking risks.

Courage is the bright aura around the best young lives. Courage in old age has to be practiced and cultivated. The tendency is to self protection. For me, racing and training to race help to slow the aging of my soul also. Riding in traffic, riding fast in groups, riding as fast as I can down a hill keeps me looking forward to the next race, the next season, and exercises my courage along with my body. Young souls can risk all for a reward, but also take risks just for the delight of feeling alive in the moment.

Countries and cultures are the same. A growing, thriving culture looks forward. A dying culture looks primarily to past glories. China and Israel, arguably the oldest countries in the world, are also the most vital. Of the 44 countries I have visited or lived in, they are the most alive. In Jerusalem, in Shanghai, in Beijing, young people are moving in.

Poland, Serbia, Hungary and Ukraine to name a few are dying. When I visited these countries the young people I talked to were looking for a way out. Those cultures are turning backward and turning inward, as we do when we die.

Am I getting old? Are you getting old? When was the last time you did something that risked you life, risked your fortune, or simply took a risk for no reason except the thrill of taking that risk?

I will leave it to my old friend to decide if he is an old soul. To call 58-year-old body with a 75-year average lifespan middle aged or not old is truly "Fake News."

America is, I believe, currently old country. As Israel and China show, a country can turn around after centuries or millennia, but right now the people in power look backward.

Money can help people and countries fight the appearance of aging, but not the fact. Nostalgia is the cosmetic surgery of rich countries. Rich, dying, countries can wrap themselves in past glories for a while. But eventually, the best young people will want to go somewhere else. And when they do, the nostalgia turns self-protective and ugly. It is happening fast and ugly in Eastern Europe. It can happen here too.

Monday, January 29, 2018

Boris Libman: The Terrible Life of a Soviet Hero

The phrase "No good deed goes unpunished" is of uncertain origin, but certainly applies to the Soviet soldier and chemist Boris Libman.

Libman was born to a wealthy Jewish family in

Latvia in the brief period between the World Wars.

Libman was just 18 years old in 1940 when the Russians invaded and made his

country into a Soviet state. During the

occupation, the invaders confiscated his family’s property and possessions and

drafted Boris into the Soviet Army.

He was seriously wounded in combat twice; the second time he was left for dead. He survived, but (as we shall see) his paperwork was not so healthy. After the war Libman applied to study at the Moscow Institute for Chemistry tuition-free as an honorably discharged disabled veteran. He was turned down because according to Army records he was dead. With months of work, he was able to prove he was in fact alive and not trying to steal a dead man’s benefits.

He was seriously wounded in combat twice; the second time he was left for dead. He survived, but (as we shall see) his paperwork was not so healthy. After the war Libman applied to study at the Moscow Institute for Chemistry tuition-free as an honorably discharged disabled veteran. He was turned down because according to Army records he was dead. With months of work, he was able to prove he was in fact alive and not trying to steal a dead man’s benefits.

In 1949 he earned a master’s degree and went to work in

Stalingrad to develop a production facility for Sarin--nerve gas. Despite his treatment by the Soviets, Libman believed in communism and wanted to help with what he saw as the defense of his

nation. Libman worked on lab studies and

on setting up a pilot plant. The main

source of information of the Soviet team was captured German scientists who

were less than fully cooperative. Libman

was not only a talented chemical engineer, but was fluent in German—a fact he

kept from the captured scientists.

Libman listened as the Germans spoke among themselves and was able to

get information that the Germans were hiding from their captors.

Most of the hardware for the Sarin plant was confiscated

from a German wartime production facility.

For the new parts, Libman had to work with Soviet producers, and so the

projected ground to a halt several times.

In the centrally planned Soviet economy, production was measured by the

weight of delivered machinery. So the

small, specialized parts Libman ordered for completing the Sarin plant were of

low priority and often poor quality. It

was a full decade before the Sarin plant at Stalingrad was in full

production. The year before, in 1958,

Boris Libman was named chief engineer at the Stalingrad plant. In 1961 he led development of a new facility

to produce Soman nerve agent. Again poor

quality parts slowed development of the plant.

By 1963, Soviet plans for war against NATO called for a surprise attack

with overwhelming use of chemical agents, including nerve gas. Libman was under considerable political

pressure to get the Soman line in production.

So he cut corners. In

particular, the Stalingrad plant had a containment pond

with toxic breakdown products of nerve agents in concentrations 100 times

acceptable levels. In February 1965,

snow melt caused flooding throughout the region. The containment pond overflowed its dikes and

spilled into the Volga River. In less

than two days the dike was repaired and no immediate problems were

evident.

But on June 15 tens of thousands of sturgeon floated belly

up in the Volga, making the river white with dead fish for 50 miles downstream

from Stalingrad. Experts determined that

it took four months for the toxins to build up to deadly levels. Outrage swept down the river and across the

region. The government needed a

scapegoat. On March 9, 1966, Boris

Libman was stripped of the Lenin prize he earned in building the Stalingrad

plant, fined two years pay, and sentenced to two years at a labor camp.

Unlike so many others, Libman’s tale does not end in a

Soviet labor camp. After just a year he

was released: the Soman plant was so complicated that the Soviets could find no

one else who could run it. Boris

returned to the land of the living once again.

In 1999 he left the Russian Federation and came to America. He lived in Philadelphia until his death a decade ago.

Some of the mess created by chemical weapons was eventually cleaned up by French chemists, including Armand Lattes.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Talking About the Holocaust After Charlottesville "Unite the Right" Rally

Nazi and Confederate flags fly together in Charlottesville, Va.

How do you talk about the Holocaust? Sadly, the events of 2017 gave me clarity I

never had before. The “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville has given me a

way to look at the Holocaust that connects with injustice in America, not only

as a terrible event that happened thousands of miles away.

A friend who is the child of Holocaust survivors told me

that she has always seen slavery as central to the Holocaust. Jews in the Death

Camps were not just murdered. They were worked till their health failed and

then murdered.

American slaves were dragged from their homes in Africa,

stripped of everything, then sentenced to permanent and perpetual slavery, a

much more cruel slavery than that in the ancient world.

In Charlottesville, the Confederate flag and the Nazi flag

marched together. The two slave and murder empires flew the flags of their

losing armies together.

In my family, our conversation about the Holocaust and

slavery began together when my daughters were in middle school. We had just adopted our son Nigel as a baby. When Nigel was between one and two years old,

I read the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin to my daughters while their cute baby

brother with the poofy hair slept in the next room.

Before reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, America’s

history of slavery, of buying and selling and owning people, was abstract. But as I read the book and Liza and her son

had to escape across the frozen Ohio River to freedom, we could talk about just

how horrible slavery really was.

At about the same time, my daughters were reading “Night” by

Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust memoir, at school.

The parallels helped us talk about what it meant to tear people away

from their friends and family and land forever, and to be treated as less than

human, less than an animal.

Nigel is now 18 and a senior in high school. We talked about

the Holocaust recently in the context of Charlottesville. The racists who want to kill and enslave Jews

rallied together with the racists who want to enslave and kill African-Americans.

Before Charlottesville, the Confederate lovers could pretend

they were just preserving their heritage. But since August, they flew their

flags with Nazis. The history of slavery and lynching and Jim Crow oppression

is not heritage, it is hate.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

"Don't Judge Me!"

The drill sergeant is judging the soldier in front of him.

"Don't Judge Me!" was a phrase I heard more and more often in the last years I served in the Army National Guard. It was often a surly young soldier telling her superior she was having a bad day and that's why her uniform, weapon, vehicle or work area looks bad.

Telling a sergeant or an officer not to judge you is like telling a wolf to be a vegan.

Not vegan......

When Jesus said, "Judge not....."it was both a warning and guide to the direction of a truly spiritual life, in the sense that it is a life emptied of concern for this world.

Anyone with expertise in this world judges others.

The essence of the warrant officer rank in the Army is someone who has considerable expertise in aircraft or trucks or weapons or administration. That warrant officer judges everybody within the world of his shop, her hangar, his range, her office.

I have walked into a maintenance building and had a warrant officer gesture toward a mechanic who was trying to replace a turbocharger on a the V-12 diesel engine that powers Patton tanks. Along with the gesture he used the warrant officer signature phrase,

"Watch this shit."

The warrant officer allowed the mechanic to almost screw up the operation, then intervened to show the incompetent soldier how to "Unfuck himself."

One of the First Sergeants I served with in Iraq told me, "I can look at a uniform and how a soldier wears it, private or general, don't matter, and tell you that [soldier's] military career."

I could not read an entire career from a camouflage uniform, but I could make accurate judgments in milliseconds about a soldier's current state of readiness for the job or mission at hand. That's what sergeants do. They judge you or they are asleep.

Judging is everywhere in life there is expertise. My rule for watching movies is I don't watch movies on subjects in which I have expertise. So I don't usually watch war movies. Too many details from wear of the uniform to weapons that never run out of ammo drive me nuts. And I judge.

So I watch movies about doctors, detectives, spies and sailors. I have no expertise in these fields, so when a spy makes a glaring procedural error that would cause a cop to cringe, I am blissfully ignorant and enjoy the show.

Of course, this judgment ability is not just to enjoy assailing the incompetent, but for survival. I race bicycles. In races and in training, bicycles ride inches apart at speeds up to 50 mph. Ten of my 34 broken bones happened in a split second at 50mph when I misjudged a pass I was making and in a few seconds was lying in a ditch bleeding with a broken neck waiting for a MEDEVAC helicopter.

Racers who ride in packs are judging each other all the time. It's a matter of survival. In a bicycle crash, the guy who causes the crash usually does not fall. The guy in front who brakes, or swerves, or drifts, clips the front wheel of the rider behind. The rider behind falls. The rider in front keeps going.

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

My Dad, Estee Lauder and Dietrich Bohoeffer

In recent months I have immersed myself in my past in a way I have never done before. For a couple of months I have been writing about my life as a soldier. I started out writing about my tank, but have since veered off into writing about Basic Training. In military life, the transition from civilian to soldier is a change beyond every other change, even the change back from soldier to civilian.

In the past year, my Jewish identity has also emerged from some vague part of my past to a very present reality.

It would surprise no one, that as I write about my military past and learn more about Judaism and my Jewish identity, that my father would appear, sometimes vividly, sometimes in a whisper. He was an American Soldier and the fourth of six sons of Jewish immigrants from Russia. (Now Odessa, Ukraine. They called it Russia.)

Among all of my family, my son Nigel has been most interested in, and my occasional companion on, my ventures exploring my past.

On Monday, the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday, we visited the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

I particularly wanted to see an exhibit that was closing soon on the Russian emigration from the Soviet Union to Israel and America and other countries from the 1960s through the 80s. After Nigel and I walked through that exhibit, we sat in a viewing area on the first floor and watched a series of two-minute biographies of prominent Americans Jews of the last century. When Sandy Koufax was on screen, I reminded Nigel that his grandfather pitched for the Reading Phillies in the 1930s. When the biography of Estee Lauder began, the soft-voiced announcer said she was born in 1906, the same year as my father.

Estee Lauder, 1906-2004

The short video traced Estee Lauder's career making cosmetics. She began her business in the 1920s and continued to grow her business though the Great Depression and on to great success in the post-war years. We watched a dozen more biographies, then took the Market Street El to 30th Street Station for the train home.

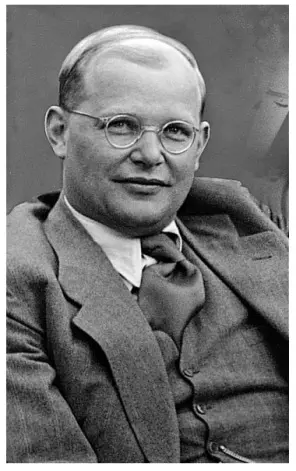

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, 1906-1945

As we waited for the train, I got an article from a Jewish activist friend about Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer was in America in the late 1930s studying American spirituality. With war looming and Hitler's attacks on Jews and other people of faith growing, Bonhoeffer left the safe haven of America in June of 1939. In Germany he organized a Church for believers who were against Hitler and then joined the resistance. In the last month of the war, April 1945, Bonhoeffer was murdered by the Gestapo in the Flossenburg Concentration Camp. He was a German who fought Hitler and died with Jews.

In December, Nigel and I had seen a display of children from the Flossenburg Concentration Camp at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York.

While Bonhoeffer struggled against the Nazis in Germany, my father commanded a Prisoner of War Camp for 600 soldiers of the German Army's Afrika Korps. My father came home to Boston after the war with my mother who he met and married during the war in Pennsylvania. In one of those odd twists of fate, I live less than 30 miles from that Prisoner of War Camp which is now the Reading Airport. Before he was commander of the POW Camp, my Dad commanded a Black Company.

And in 2018, the Black grandson my Dad never met--George Gussman died in 1982--went to a Jewish museum on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to learn about his family's history.

My father and Estee Lauder were both children of immigrant Jews born in America in 1906. They lived long lives because their parents came here, leaving countries that would be crushed by Hitler in the 1940s. In that same year, 1906, a leading German family of scientists and thinkers added a son who would become a famous man of faith. Bonhoeffer was offered shelter in America and turned it down to return to his people.

These three lives share only a birth year and the admiration of a son and grandson who learned a little more about courage and the best of America on a day devoted to an American hero.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Twelve Windows into History: A Year of Reading History Books in 2025

In 2025, twelve of the fifty books I read were histories. Together they spanned continents, centuries, ideologies, and genres. Some were s...

-

Tasks, Conditions and Standards is how we learn to do everything in the Army. If you are assigned to be the machine gunner in a rifle squad...

-

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day is, on the surface, a beautifully restrained novel about...

-

On 10 November 2003 the crew of Chinook helicopter Yankee 2-6 made this landing on a cliff in Afghanistan. Artist Larry Selman i...

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/c4/de/c4de96fb-9044-400e-8271-56fda2455b59/jewish_refugees_aboard_the_ss_st_louis_in_cuba.jpg)