I had a few people who read this post ask me about the rest of the list, so I am going to add the additional titles with only an occasional comment. They will be in my arbitrary categories.

The list below represents the best and the worst of the 52

books I read in 2017. Only two of the books were published this year. The

majority of the authors are alive and I went to readings by two of them.

I am an obsessive reader; both in wanting to

read and in trying to read everything by an author I love.

In that regard, 2017 was a wonderful year

because

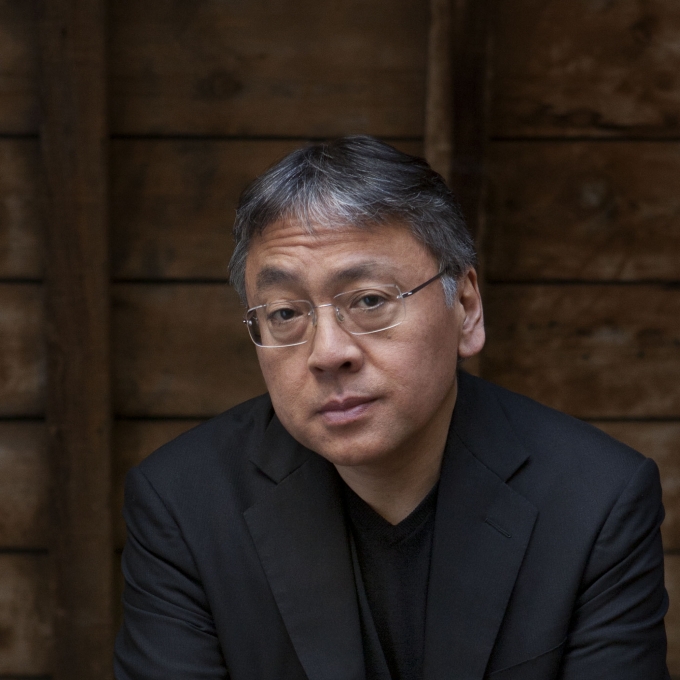

Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize in literature. I started reading him

four years ago and in a few days will have read all of his novels and stories.

The last book,

The Unconsoled will be

on next year’s list.

All the links are to the author's page or a page about the author. I picked a book or two in each of the categories I sorted them into.

The recommendations are brief. Each of those books I believe are worth reading for anyone interested in that kind of book. I wanted to write only enough to say, "This is great!" But the last review, the book I did not like, goes on for a thousand words. If you have not read the book, it will be dull since it refers to specific disagreements I had with the author's assertions, and I do not present his side of the argument. Enjoy! Except the last one.

Poetry

My largest category this year by number of books was poetry

at 13 books.

The best book in this

category is, for me, the completely predictable choice of

Inferno by Dante Alighieri.

This is my eighth time reading this first book of the

Divine Comedy but the eighth different

translator, this time the Lombardo translation.

It is good, but I still like the Pinsky translation best.

This time, because I was in a class studying

Dante, I read aloud and listened to

Roberto Benigni read all of the cantos. I

never read the Italian before.

I

recommend it, just for the sound.

After Dante, the next best was

Nativity Poems by

Joseph Brodsky. An émigré communist Jew writing

on the theme of the incarnation was not just a one-time crazy idea, Brodsky

returned to the theme of nativity throughout his career. A lovely collection.

The rest of the poetry list:

I also read Brodsky's

Selected Poems and two other volumes titled

Selected Poems by Vladimir Nabokov and Boris Pasternak.

Staying with Russians, I read

Veronezh Notebooks by Osip Mandelstam and a collection titled

Four of Us with poems by Mandelstam, Pasternak, Anna Akmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva.

The Bad-Tempered Man a comedy by Menander

How We Must Have Looked to the Stars by Alysia Nicole Harris

Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics by C.S. Lewis

Some Ether by Nick Flynn, which is a memoir in poems

Poetry Handbook by Mary Oliver

In Flanders Field poems about World War I by several poets.

Fiction

The best of eleven works of fiction I read was

Identity by

Milan Kundera, or

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which

I read a week later.

I had never read

Kundera so seeing the world through the eyes of his obsessive, alienated

characters was lovely.

These two books

also represent two phases of his life.

Unbearable

Lightness was written when he lived in Prague in what is now the Czech

Republic.

Identity was written in

Paris after he left the Eastern Bloc for the west. I was in Prague and Paris

this summer so the two books helped bring back these two lovely cities in my

mind.

Also wonderful:

Dr.

Zhivago by

Boris Pasternak. If you only saw the movie, read the book. It is

so beautifully told and the poetry in the novel was so good, I next read a

volume of Pasternak’s poems.

In addition to Identity, I read two other books originally written in French:

The Lover by Marguerite Duras

Femme Fatale by Guy de Maupassant

And two books in French

D'Artagnan by Alexandre Dumas, an abridged version for middle/high school

Il Etait Une Fois three Once Upon a Time stories

Two novels about the Vietnam War by Tim O'Brien:

If I Die in a Combat Zone

The Things They Carried

I read a funny book titled Greek and Roman Comedy by Shawn O'Bryhim

Another Russian novel The Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin, a book that is dark and funny and violent and so entertaining.

Finally How I Learned to Drive a play by Paula Vogel. A strange and compelling play. I could not put it down.

Memoir

I read eight memoirs this year, but the one that spread into

my soul and will not let go is

Survival

in Auschwitz by

Primo Levi.

I read

this book a couple of months before visiting Auschwitz and seven other

concentration camps and Holocaust memorials. When a book conjures a nightmare,

no two readers will have exactly the same terror.

In my case, the most vivid and painful of all

the stories was the man who had earned the Iron Cross for gallantry under fire

in World War I and thought his bravery proved his patriotism.

Even though he earned the equivalent of the

American Congressional Medal of Honor, he was a Jew; he went to the gas

chamber.

Since Trump’s election, I have

had several people tell me that I have nothing to worry about because I am a

veteran.

But the men who marched in

Charlottesville chanting “Jews will not replace us” would kill any Jew, veteran

or not.

I also read three memoirs by

Nick Flynn. The best was a short collection of poems

called

Some Ether. The other two by Flynn were Another Bullshit Night in Suck City and Reenactments a memoir about making a movie about the other memoir. I listened to Flynn speak and met him after his reading. He is about my age and grew up near where I grew up. It is funny he is a memoir writer. His books and presence reminded me of being beaten up by Irish kids when I was in grade school.

Gamelife by Michael Clune

The Folded Clock by Heidi Julavits

Tiny Beautiful Things by Cheryl Strayed

Why I am so Clever a funny little book by Friedrich Nietzsche

My Fellow Prisoners by Mikhail Khodorkovsky. This last one is a prison memoir in character sketches of fellow prisoners written by the first billionaire Putin jailed, way back in 2003. He got 10 years.

History

Six Days of War by

Michael Oren topped the short list of four history books I read this year. It

is the story of the stunning victory of Israel over Egypt, Jordan and Syria in

that order. Israel was outnumbered 100 to 1 and beat three bordering Arab

nations in sequence in roughly two days each.

The book shows how the blindness of arrogance can lead armies with

overwhelming numbers in men and equipment to ignominious defeat.

If you wonder how a small army can defeat a

huge one, this book shows every step in how Egypt took every advantage they

possessed and threw it away. It also shows how reluctant allies can be almost

as bad as enemies.

Syria especially held

back in a way that assured the defeat of Egypt and Jordan.

I began the year reading the book

Band of Brothers by

Stephen Ambrose. The book is the basis of the HBO series of the

same name, which is my favorite video production on war. The book is good, but

there is nothing better than the HBO series.

Lenin's Tomb by David Remnick. The last days of the Soviet Empire.

Histories by Herodotus, Book V partly in Greek, partly in English.

Politics

I was going to highlight

On

Tyranny by

Timothy Snyder as my top politics book for 2017.

But I am going to re-read it in 2018 along

with

The Prince by

Machiavelli.

Both books in their own way are handbooks on

how politics really works. Machiavelli advises the prospective leader on how to

take and keep power, Snyder tells the rest of us what to do when a tyrant is

taking control. If Robert Mueller is fired in 2018, Snyder will be the top of

my list next year, assuming ordinary citizens are allowed free use of the Internet.

With Snyder pushed to next year, I will turn to

American Vertigo, one of two books I

read this year by

Bernard-Henri Levy, French Philosopher who travels the most

dangerous corners of the world writing and producing movies about cultures in

conflict.

He has written about Libya,

Syria and much of the Arab world with insight and empathy rare in any writer,

but all the more in Jew born in the rubble of France after World War II.

In

American

Vertigo Levy reprises the journey of Alexis de Tocqueville took in 1831.

Tocqueville planned to write about prisons in America, which he did, but then

wrote arguably one of the top political works ever, one still quoted by

Americans of every political affiliation.

Levy begins in Rikers and winds across our continent to Alcatraz and

loops back through the South.

It really

is a delightful view of America, by a visitor clearly delighted with America.

I read another book by Levy, which is the best book in my

last category.

How to Cure a Fanatic by Amos Oz

Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit

Science

This year I read some of the best science books I have read

in years, maybe ever!

The Gene: An

Intimate Story by

Siddhartha Mukherjee wove together the entire history of

the gene with Mukherjee’s family history and the cultures he inhabits.

Improbable

Destinies by

Jonathan Losos gave me the clearest explanation of the

interaction between natural selection and chance.

I also read Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel which is a social science or psychology book.

But by far the best was

Sapiens

by

Yuval Noah Hariri.

The last time I

was this delighted with a history of science book was

Guns, Germs and Steel the Pulitzer Prize winning book by Jared

Diamond.

Sapiens recounts the full history of the rise of Homo Sapiens from somewhere

in Africa to literal world domination. The early bloodthirsty success of our

species is fascinating.

Unlike other

human species, we could cooperate in groups as large as 500 to trap and

slaughter large species. We wiped out mastodons, saber-tooth tigers and many

other large species across the globe and in a bit of multitasking, wiped out Neanderthals

and every other humanoid species.

After

explaining our proficiency in communication and killing, Hariri contends our

hunter-gatherer life was much better than the lives most sapiens lived after

the rise of agriculture 10,000 years ago. When agriculture arose, a few

benefitted, but many had shorter, more brutal lives of servitude and disease.

From there he takes us right to the present

with the rise of culture and shows why tribalism persists.

I am reading this book again next year.

Faith

My last category is Faith.

For someone like me with a believer’s turn of mind, every book has a

faith dimension of some sort. The Divine

Comedy is a poem, but is also a map of the Catholic view of the universe,

physically and spiritually. Every memoir implies life has meaning and value and

significance.

The book explicitly on faith that moved me the most was The Genius of Judaism by Bernard-Henri

Levy. This book looks at the history of the Jewish people and Israel through

the lens of the Book of Jonah. Levy

shows us Judaism and his view of the Jewish world by his interactions with

“Nineveh” in the form of modern-day enemies of Jews and Israel. One modern Nineveh he visits is Lviv,

Ukraine. I knew my trip last summer was

to visit Holocaust sites would center on Auschwitz, but this book led me to

pair Lviv with Auschwitz as two sad extremes of the Holocaust. Auschwitz is the most industrial site of

slaughter, Lviv is the most personal. At

Auschwitz, the Nazis built a place of extermination. In Lviv they simply

allowed the local population to act out their own anti-Semitism. Lviv was the most personal of the sites of

Holocaust slaughter. Neighbors killed

neighbors and dumped their bodies in ditches.

Levy went to Lviv to make peace with this site of unbridled hate. He seems to have succeeded. I did not.

Ukraine tried to kill my grandparents. Ukraine remains a cauldron of

anti-Semitism.

Overall, the book left me wondering about my identity as a

Jew. The book helped me to decide that I could reconnect with the Jewish part

of me in a positive and growing way, a process that began last spring and is

still going on as the New Year begins.

From the well of hope that Levy opened for me, I will now

turn to the dry, barren waste of

Rod Dreher’s book

The Benedict Option.

When you want to say the nation is going to Hell, you first

need a villain. Then you need to say how that villain is going to ruin

everyone’s lives. The central theme of The

Benedict Option is Dreher predicting the end of Christian culture in

America through gay rights and the gay agenda. Dreher is sure that Christian

hegemony in America is over. The only option is to withdraw from life in

corrupt America into intentional communities of those committed to real

goodness.

The first question I have is, ‘Why will the gay agenda ruin

our nation after it flourished with a long history of slavery, Jim Crow and

betrayal of Native Americans?’ Is a nation really blessed by slavery and genocide and cursed by gay marriage?

America perpetrated the worst slavery in the history of the

world on Africans. They were kidnapped and brought here in chains to be slaves

until death for generation after generation. America had slavery with no hope

of buying oneself out or getting free. The center of that slavery was the New

Orleans slave market.

Dreher grew up in Louisiana and returned there to withdraw

from life in big cities. He is in a

state and a region with a horrible history of slavery, followed by 100 years of

apartheid called Jim Crow. What could be worse than men who would buy and sell

human beings, fight a war to keep their slaves, and then oppress their victims

openly for a century after losing the war?

Every confederate battle flag represents unrepentant racism,

slavery and murder. And yet, Dreher

says, it is gay rights that will kill Christian faith in a way that Pride,

Murder, Rape and Greed could not. Dreher says at the end of the book historians

will wonder how a 3% minority killed a great nation like ours.

If America can perpetuate slavery longer than every

civilized nation, break uncountable treaties, slaughter Native-Americans, allow

Jim Crow laws in the south for a century, and then put a racist sexual predator

in the White House with the support of 81% of "Christian" America,

can the Gay agenda really trump everything else we have done? Dreher has his

enemy.

Dreher begins the book saying he was led to the idea of

withdrawal from culture by thinking of his son’s future from the moment he was

born. The book has many instances of

Dreher and other Christian parents making what he calls sacrifices for their

children. Dreher writes as if parenting

were the central Christian ministry. As

a father of six, I would say parenting is one of the central delights and urges

and vanities of the Human Condition. Can

any parent really say that spending their time and money toward the success of

their children is a sacrifice? Does

working toward the success of my own children make me the equal of Mother

Teresa caring for the poorest outcasts in a Calcutta gutter? No, it doesn’t. My bright, successful, funny

children are a delight, they are not a ministry. And they in no way set me apart from the

world.

I heard many idiots in focus groups and on the news say one

proof that Trump was obviously a good guy because he is a good father whose

children love him. Saddam Hussein loved

Uday and Qusay. The worst Roman emperors were the beloved, spoiled children of

previous emperors. Trump is, by his own

words a racist who is willing to grab other people’s children by the pussy.

Parenting does not excuse pandering.

Dreher should know well that nothing ties a person to the

world like having children. No actual

Benedictine has kids. The withdrawal

from the world with kids that Dreher posits is not a new monastic movement, but

a gated community with spiritual decorations on the iron fence.

Compared to, say, Coptic Christians in Cairo and other

believers facing danger and death, the Benedict Option like a military video

game, allowing the out-of-shape, pale player to pretend he is a combat soldier

while in the comfort of mom’s basement away from the blood and bullets of

battle.

I would have called it the book the Benedict Fiction.

-->

A category I did not list was language. I don't expect these books to jump on anyone's 2018 list.

Language Learning

Между Нами a Russian textbook.

English Grammar for Students of Russian by Edwina Cruise (no relation to Tom Cruise)

Introduction to Greek by C.W. Shelmerdine

That's the Whole List!

-->

-->

-->