The thesis statement of Understanding Beliefs is in the middle of page three in the first chapter:

One of the most important things to say about beliefs is that they are (or at least should be) tentative and changeable.

From this statement, many believers and all fundamentalist believers, would disagree with Nils J. Nilsson, Kumagai Professor of Engineering (emeritus) at Stanford University. He was a pioneer in computer science and robotics and wrote many books including The Quest for Artificial Intelligence: A History of Ideas and Achievements. Nilsson died in 2019 at the age of 86.

Nilsson first divides beliefs into "procedural" and "declarative." Procedural beliefs are what we know and believe by doing--riding a bicycle for example. Declarative beliefs are those we state in sentences--religious creeds, political views, etc. He then discusses whether declarative beliefs constitute knowledge. Some who do research in the field of knowledge say that beliefs are different, Nilsson says in the introduction that beliefs cannot be separated from knowledge. Then he begins the first chapter:

Our beliefs constitute a large part of our knowledge of the world. For example, I believe I exist on a planet that we call Earth and I share it with billions of other people.

He goes on to enumerate his beliefs in things such as computers and airplanes, beliefs about our culture such as democracy and the rule of law, and beliefs about the members of his family. He describes procedural and declarative belief in more detail and explains scientific theories. The Nilsson says,

Before we trust a belief sufficiently to act on it, we can analyze it and perhaps modify it--taking into account our own experiences, reasoning, and the opinions and criticisms of others.

Which had me smiling and thinking of religious believers, myself included, who are more likely to believe and then analyze later. He ends the chapter saying we are like pilots flying through clouds trusting our instruments--our beliefs guide our lives when we cannot see our path.

The second chapter asks the question "What do beliefs do for us?" The answer:

Our beliefs serve us in several ways. Some help us make predictions and select actions, some help us understand a subject in more detail, some inspire creativity, some generate emotional responses, some can even be self-fulfilling.

The rest of the chapter explains more about what beliefs do for us. In the third chapter we get to the more murky subject, "Where do beliefs come from?" Part of Nilsson's answer:

All of our beliefs are mental constructions. Some are consequences of other beliefs, and some are explanations built to explain existing beliefs and experiences. (Italics Nilsson's.). ... We do know that explanations can only be constructed from the materials at hand--that is, from whatever beliefs and concepts happen to be around.

Chapter four "Evaluating beliefs" looks at how we handle doubt in our beliefs and the strength of our beliefs. His example throughout the chapter is belief in global warming or climate change. How those who believe come to that belief and how to evaluate that belief given the new evidence every year. He worries about those who will not evaluate their beliefs:

On many things, our minds are made up. But they can only be made up if we never challenge them with new experiences, new information, and discussions with knowledgeable people who might hold opposite beliefs. ... Changing our minds is difficult, but it is necessary if we want to have ever-more-useful descriptions of reality.

Chapter five "In all probability" explains how we show confidence in our beliefs, or not. Most of our beliefs, fall between the extremes of "definitely true" and definitely false" and this chapter explains how to determine our confidence in a particular belief.

Chapter six "Reality and truth" explains the boundary between reality--things that exist, and truth--statements about what actually exists. That boundary, like an open border, gets crossed a lot. Nilsson says, In the time of Galileo "even some theologians agreed that there was a difference between reality itself and descriptions of reality."

Nilsson uses coal as an example. Is coal black? Is the color of coal characteristic or part of the reality of coal? Which led me to think of titanium dioxide. In nature it is black sand covering beaches in around the world: in Brazil, in South Africa, and in Western Australia among others. Titanium dioxide is black when it forms in nature. Almost a century ago, someone figured out a process for oxidizing titanium under controlled conditions that results in a molecule 2,500 Angstroms in length--half the wavelength of white light. The result is the whitest possible white pigment.

Chemically, black sand and white pigment are identical. But when the molecule is 2,500 Angstroms in length, our eyes see white, vivid white. When the molecule is much bigger, it appears to be black. Is the same substance both white and black? In this case appearance is physics not chemistry. Is the reality the chemical compound or the color? Are white and black appearance only, or reality?

Chapters seven and eight describe "The Scientific Method" and "Robot Beliefs." They are fun but for those committed to the scientific method, that chapter is a review summed up when Nilsson says, "People have a lot of beliefs that are not falsifiable, and therefore such beliefs are not scientific." Nilsson explains the current state and limits of artificial intelligence and robot beliefs. He ends the chapter saying, "Robots do not have any "magical," nonphysical methods for obtaining information. I don't believe humans do either."

The final chapter is "Belief Traps"--getting trapped in beliefs that wouldn't survive critical evaluation. Nilsson begins the chapter:

I have stressed throughout this book that our beliefs should be subject to change. Scientists are used to having their theories replaced by better ones. Why shouldn't we regard our everyday beliefs as tentative also?

In the next paragraph, it is clear he knows why. He says, "Let's looks first at obstacles to belief change caused by one's lifestyle and attitudes." He then cites the isolation of technology as a cause of falling into belief traps. He then quotes a psychologist who says "People are credulous creatures who find it very easy to believe and very difficult to doubt." He ends the chapter and the book quoting John Stuart Mill:

[the person who] has sought for objections and difficulties instead of avoiding them, has shut out no light which can be thrown upon the subject from any quarter...has a right to think his judgment better than that of any person, or any multitude, who have not gone through a similar process.

QED or Amen, as you prefer.

Understanding Beliefs is part of The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series, dozens of books on topics from Free Will to Nuclear Weapons and many more. I have read four and plan to read three this year.

First nine books of 2022:

1776 by David McCullough

The Life of the Mind by Hannah Arendt

Civilization: The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson

How to Fight Anti-Semitism by Bari Weiss

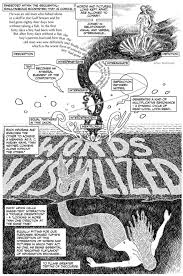

Unflattening by Nick Sousanis

Marie Curie by Agnieszka Biskup (en francais)

The Next Civil War by Stephen Marche

Fritz Haber, Volume 1 by David Vandermeulen