A new friend here in Panama, a cyclist, Yogi, and round-the-world-sailor named Roger, asked me for a list of books I would recommend. He is an avid reader and looking for new books he has not read.

Roger has read all the greats of 19th Century Russian literature. Today I found out why. Roger was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan in 1970. He took a

semester of creative writing with Joseph Brodsky, the Russian emigre poet who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1987. Roger won the Russian lit. professor lottery!

I have a few books with me in Panama. Two are Blindness, the terrifying dystopian novel by Jose Saramago, and Tribe by the journalist and war correspondent Sebastian Junger. Both are excellent, so I gave them to Roger.

Now the list.

1. Kazuo Ishiguro. Remains of the Day and Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro are my favorites. I have read everything Ishiguro has written, most recently Klara and the Sun and seen his movie Living. His writing is brilliant. These two books are my favorite.

2. Hannah Arendt. Philosopher and historian and one of the most influential political writers of the 20th Century. Born in 1906, a German Jew, she earned a PhD at Heidelberg in 1929 and fled Germany in 1933 just after the Nazi takeover. She lived in France until WorldWar II began, then escaped to America in 1941. In 1951 She published The Origins of Totalitarianism, her best-known work defining the new tyranny of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. I have read all of her books. I most admire On Revolution a book that shows why nearly all revolutions devolve into tyranny, but America did not. I love The Human Condition for explaining living in our world. I am such a devoted fan, I am in a weekly reading group and go to Hannah Arendt Conferences.

3. George Orwell. I have read and re-read Orwell's novels. A decade ago I read the 1200-page volume of his collected essays, finding endless entertainment. His essay on brewing tea shows the utter snob that still lingered inside the Democratic Socialist writer. There is no better book explaining the rise of Stalin than Animal Farm. A decade ago, I became convinced that 1984 was not prophetic after all, until I read about life in Communist China.

4. Mark Helprin. I have been a devoted fan of Mark Helprin since read his novel Winters Tale in 1983. I have since read every one of his novels, most recently The Ocean and the Stars. His Paris in the Present Tense gave me a new and lovely view of my favorite city. I plan to read Winters Tale for the third time this year.

5. - 12. I love big books in which one author writes the entire history of humanity as in Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari.

Or of recorded human history as in Why the West Rules--For Now by Ian Morris or another view Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond.

Or a history of American from the view of those without power, These Truths by Jill Lepore.

Another delightful view of the past 500 years Civilization: The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson.

I recently read Titans of History by Simon Sebag Montifiore. I plan to read his The World: A Family History of Humanity. But I also want to read his Jerusalem.

An aside on these books is that I believe recent histories are the best. The old histories did not have access to all the new data. That perspective here.

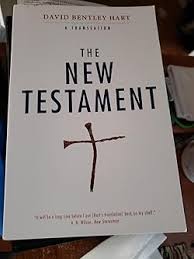

And another aside! If you read books in translation, read the newest translation available. The latest translation will be clearest and will correct the mistakes of predecessors. If you read Scriptures in translation, read a translation by one person. A committee compromises. One person may be wrong, but they won't be tepid.

Back to the list.

13. (for the unluckiest author on this list) The Forgotten Soldier by Guy Sajer. Son of a German father and French mother from territory between the countries. Enlists in the German Army at 17 in 1941. Spends the entire war in Russia. Returns home. Home is now in France. He serves in the French Foreign Legion to avoid prison. A soldier under any flag can be a good soldier.

14. The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli I re-read it for the tenth time last year, every Presidential election year since 1980. I will read it again in 2028. Machiavelli's advice remains brilliant, relevant and chilling 500 years after he wrote it.

15. Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin. A 2006 novel that imagines Russia in 2028 as a restored Tsarist empire, complete with Oprichniks, the assassins of Ivan the Terrible. It is a crazy, funny novel, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine showed it has a dark, prophetic side.

16. A Canticle for Liebowitz by Walter Miller Jr. shows us the world after a Soviet-American nuclear exchange kills 95% of the population. A Catholic monastery in the ruins of Utah preserves books after the survivors of the nuclear war burn books and scientists. The irony in this book is amazing.

17. Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville. In a nine-month trip beginning in1830, Tocqueville found the heart of American democracy and wrote a book that became the central description of America for the world--including every political scientist in America. He said in the 1830s that the 20th Century would be defined by the conflict between Russian and America.

18. C.S. Lewis. I have read all of the 39 books he wrote in his lifetime, plus posthumous collections. His novel Till We Have Faces is so good it is one of the books I read aloud to my daughters. The central characters look at the same thing at the same time and see two entirely different things. So much of the book looks at perception and reality in ways I have not read anywhere else. His book The Four Loves gave me a frame for seeing the different ways people express love...and reject love.

19. Vasily Grossman. Since Roger has read about and is very interested in the Battle of Stalingrad, my first recommendation is Life and Fate the novel of the Battle of Stalingrad and it's second volume titled Stalingrad. Grossman was a Soviet war correspondent who arrived the first day of the battle and reported then entire terrible fight.