The Life of the Mind is the last of more than a dozen books written by Hannah Arendt in her life. This book consists of two book published in a single volume, the first part on Thinking, the second on Willing. She finished Willing on a Sunday and died the following Thursday. In her typewriter was the first page of the third volume which would have been titled: Judging.

We finished a months-long discussion of the book with a review session. I have been part of the Virtual Reading Group of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College since 2018 when I attended a conference on anti-Semitism. The group meets weekly on Zoom with upwards of one hundred participants each week.

In Thinking Arendt describes the activity of thinking as an inner dialogue. When thinking we withdraw from the world. She opens the book talking about how in our ordinary lives we are in the world of appearances. We present ourselves to others in what we say, what we wear and what we do. These appearances, to the extent they are within our control, are the way we present ourselves to the world. These appearances may or may not represent reality, either what we believe to be our true selves or what we others believe.

Arendt talks about how the age of scientific discovery ended the Common Sense people had. In the 16th and 17th Centuries, an avalanche of scientific discoveries overthrew previous understandings of the world. I read a book last year titled Being Wrong that has a lovely description of how we can't trust how the world appears. And the rest of Being Wrong is about how hard we will fight to be right.

Thinking allows us to withdraw from the unreliable world of appearances into a place where we can consider possibilities. Thinking always involves language, even when we consider images: thinking beings have an urge to speak, speaking beings have an urge to think.

She contrasts thinking with action: persuading through speech. When we speak, when our goal is clear, there is no inner dialogue. We say the words that will express our thoughts.

In Willing Arendt shows acts of will to be the opposite of thinking. When we think, we deal with what has happened, with the past. In willing, we decide to project ourselves into the future. There is an inner dialogue of urging, especially when there is hesitation, but the dialogue is toward an action in the future.

Arendt shows the development of the concept of will in western thought using those she considers the philosophers of the will. In her view, the Ancient Greeks never developed a concept of the will. She credits the Apostle Paul with making clear the function of the will in the life of the mind. She moves from Paul to Epictetus to Augustine to Aquinas, then has a chapter on Duns Scotus. A contemporary of Aquinas, Arendt describes the philosophy of Scotus as the "primacy of the will." She credits him as being the most clear philosopher of the will among all those she introduces. I have read nothing of Duns Scotus and found this chapter fascinating.

The best philosophy brings clarity to life. I know so much more about thinking and willing than I did before reading and discussing this book. If you are interested in the Virtual Reading Group, contact the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.

First seven books of 2022:

Civilization: The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson

How to Fight Anti-Semitism by Bari Weiss

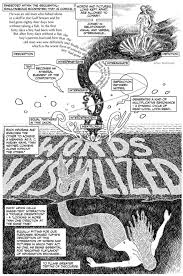

Unflattening by Nick Sousanis

Marie Curie by Agnieszka Biskup (en francais)

The Next Civil War by Stephen Marche

Fritz Haber, Volume 1 by David Vandermeulen